The Ethics of Nearness

If weekends and vacations occupy your mind when you are at work and when you are not at work your mind is occupied with work, are you ever anywhere? The ethics of nearness is made up of two concepts, proximity and presence.

Proximity

A culturally relevant way to illustrate proximity is the murder of George Floyd. Proximity is simply nearness in space, time, or relationship. In the context of ethical proximity, which refers to obligations based on closeness, Derek Chauvin, the officer who was convicted of Mr. Floyd’s murder, had the highest duty to Mr. Floyd, he was nearest.

The surrounding Minneapolis police officers probably had the next highest duty to Mr. Floyd, they were, at best, a few feet away.

Seventeen-year-old Darnella Frazir, a bystander, was further away but close enough to have a duty to Mr. Floyd. She said that she was walking home from the store with her younger cousin when she saw Floyd being pinned to the ground by Chauvin. She started recording the incident on her phone, and she continued to record even after Floyd stopped moving.

Another bystander, Alyssa Funari, tried to intervene, but she was told to back away by one of the police officers so she called 911 three times.

The bystanders didn’t stop serving Mr. Floyd when he died. They played a vital role in bringing attention to the injustice and their videos and their testimony helped to ensure that Chauvin and the other officers were held accountable for their actions.

Others who were close to the incident simply stood by and watched.

Historically, relationships developed in close-knit communities where people were not just physically close but also emotionally and morally connected. The physical proximity wasn’t just about space; it was the foundation upon which trust, understanding, and shared experiences were built.

Moreover, when we engage with someone physically present, our ethical proximity to them inherently becomes intensified. The very act of sharing a space amplifies our responsibility to acknowledge, respect, and respond to them with our undivided attention. This isn’t just about courtesy; it’s about recognizing the depth and immediacy of the bond that shared physical space creates.

Presence

It is quite possible to be physically near, or in a close relationship, but not be present. The ethics of presence, emphasizes the significance of being genuinely engaged in the current moment.

It is pretty common to be with someone who is always lifting their wrist to their face to check their smartwatch. Or being on a video call while, at the same time, reading notifications and checking text messages. Digital interactions, while enabling vast and immediate connections, often lack the depth and nuance of face-to-face communication. Think of it this way: When in the same room with someone, you’re privy to a multitude of non-verbal cues – a slight change in tone, a fleeting facial expression, the subtle language of the body. These cues, often imperceptible in digital interactions, enrich our understanding of the situation and the person, grounding our response in a more holistic perception.

While digital spaces allow us to bridge vast distances and connect with a diverse array of individuals, they also introduce a level of detachment. I sometimes wonder if we have replaced connection with the illusion of connection. The immediacy of physical presence is replaced by screen-mediated interactions, where responses can be calculated, edited, and sometimes devoid of genuine spontaneity. The argument isn’t that digital interactions lack authenticity, but rather that they exist within a framework that doesn’t always lend itself to the depth and immediacy that face-to-face interactions inherently possess.

Contrast that with a friend I have who is losing his hearing. For the most part, he is quiet. But when he wants to know something, he stands right in front of me and gets close so he can hear best and watch the words my mouth form. He is present.

The Ethic of Nearness

The ethic of nearness combines proximity and presence. It certainly comes into play when we choose to be with someone. When I was a child, we would often take the phone off the hook during supper time so that we could give our full attention to the people at the table. We avoided visiting neighbors during the supper hours. One person talked at a time so that we could fully honor what they were saying.

The ethic of nearness might also come into play just because we are proximate to someone, whether we invited them or not. Those people, for example, start a conversation with someone who is standing on a bridge about to jump.

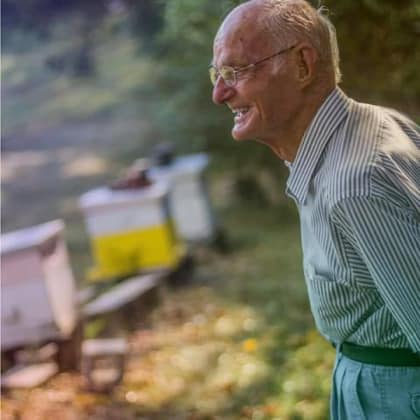

When I think about a way to illustrate the ethic of nearness, Carlton Bearden comes to mind. He was a fellow beekeeper and 102 years old when he died this week. Several years ago, I took a group of students to Mr. Bearden’s home so they could see his apiary and hear what he had to say about honeybees. He didn’t disappoint. He gave the students a hive tour, let them go into his honey house, and showed them several things he had invented that improved bee health and honey production.

When I think about a way to illustrate the ethic of nearness, Carlton Bearden comes to mind. He was a fellow beekeeper and 102 years old when he died this week. Several years ago, I took a group of students to Mr. Bearden’s home so they could see his apiary and hear what he had to say about honeybees. He didn’t disappoint. He gave the students a hive tour, let them go into his honey house, and showed them several things he had invented that improved bee health and honey production.

When we went into his house, he sat in a chair in the den and the students sat around him on every flat surface, mainly the floor. The first few questions were about bees and honey, but then one of the students asked, “What is this book you have open in the stand over here?”

“That is my bible,” Bearden replied.

“Why is it open?”

“Well, that is how I start my day.”

“How does that start your day?” another student asked.

“Well, I start my day by reading a little from the bible, so far, I’ve read through it four or five times. Then I pray.”

“What do you pray about?” yet another student asked.

“Well, I pray for my family and friends, my neighbors, my state, and the world.” Mr. Bearden replied.

He practiced proximity.

For the next hour or so, students shared their stories about bees and things that taste sweet, family, friends, and neighbors. Mr. Bearden listened and asked questions when he didn’t understand. When asked, he talked. Everybody was proximate and everyone was present. Nobody was left out. There were no interruptions.

Mr. Bearden understood the ethic of nearness. He experienced it. Consider these lyrics by Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart:

You’re nearer, than my head is to my pillow,

Nearer, than the wind is to the willow.

Dearer, than the rain is to the earth below,

Precious as the sun to the things that grow.

You’re nearer, than the ivy to the wall is,

Nearer, than the winter to the fall is.

Leave me, but when you’re away, you’ll know,

You’re nearer, for i love you so!

Beekeepers experience the wind blowing through willows, and rain melting into the earth and the sun touching things that grow. It is part of the art and skill of beekeeping.

Later, one of the students asked me why they felt closer to Mr. Bearden than their own grandfather. After all, they had only spent an afternoon with Mr. Bearden and they had known their grandfather their whole life. I encouraged the student to keep thinking about it, but I knew the answer. In that short time, Mr. Bearden was near.

###

- Inviting Human Flourishing Through Building Design - March 22, 2024

- The Message in Your Misfortunes - January 28, 2024

- The Right of Self-Determination - January 15, 2024